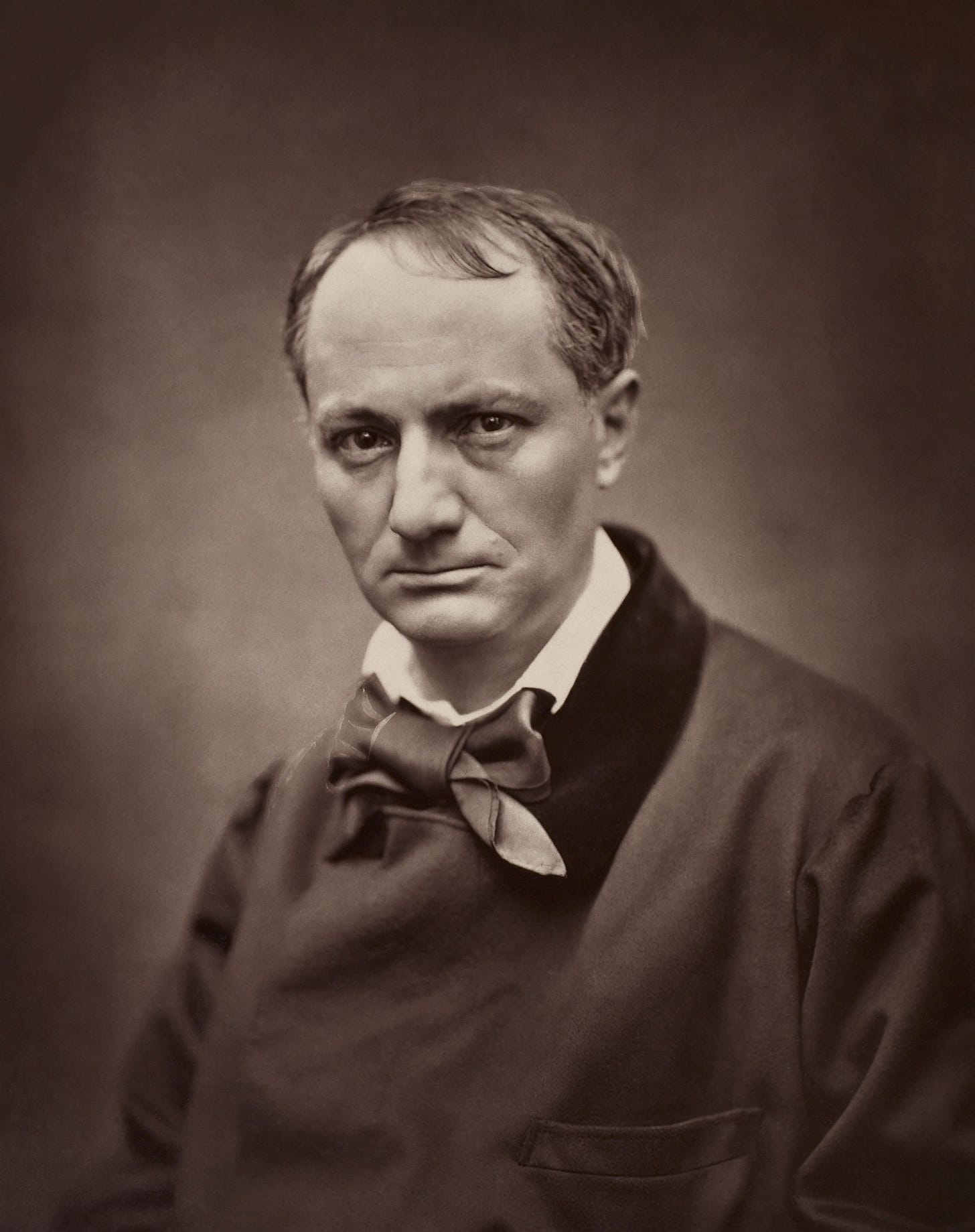

Last week, Nietzsche taught us that we have to read slowly. To read slowly is to read with Hintergedanken and with furtive, skeptical glances cast both forwards and backwards to see if something is amiss. While our subject last time was the media theorist Friedrich Kittler, today it is another author it often pays to read very slowly, namely Charles Baudelaire. More specifically, we’ll be taking a look at one of his many rants on women, something that might be strangely topical in a world where male rancour towards women appears to be on the rise.

We will not be looking at one of his famous poems like ‘Une Charogne’ (‘A Carcass’). Here I provide some stanzas in prose translation:

Remember the object we saw, my love, that sweet summer morning: where the path turned, a sordid corpse on a bed of gravel,

Limbs up in the air like a woman given to lechery, boiling and sweating with poison, opened up in a nonchalant and cynical manner its belly full of fumes.

The flies were buzzing around these bowels out of which came black battalions of maggots that flowed like a thick liquid along these living rags.

—And no less will you yourself turn out like this horror, like this terrible pestilence, star of my eyes, sun of my world, you, my angel and my lust!

(‘Une Charogne’, stanzas 1, 2, 5 and 10; the French original is that of the 1861 edition of Les Fleurs du mal)

Instead, we will turn to some of his less read prose writings. In this, it’s not just Belgians that are given a hard time, but also women. For instance:

Pourquoi l’homme d’esprit aime les filles plus que les femmes du monde, malgré qu’elles soient également bêtes ? — à trouver.

(Mon coeur mis à nu, folio 34)

Why does the man of intellect enjoy girls more than worldly women despite the fact that they are equally stupid? — something to figure out.

Here is the misogyny of Baudelaire on full display, perhaps even a touch of paedophilia à la Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert? But then again, maybe not, because that would be reading a lot into a potentially quite polysemous term. So let’s unpack this.

Immediately, I’m wondering about three things: what is a ‘man of spirit’, which is what homme d’esprit literally means, though I translated esprit with ‘intellect’; what does ‘girl’ mean here, and what is a ‘woman of the world’.

These three things relate to each other. So a femme du monde is a ‘worldly woman’, which is to say a woman who has seen the world and who is sophisticated. There’s also a clear connotation of this being somebody who moves in high society, suggested by related adjectives like mondain, which means ‘related to high society’.

This helps explain the contrast to fille, ‘girl’. As with English ‘girl’ and ‘woman’ (or ‘boy’ and ‘man’ for that matter), the terms femme and fille do not turn on age alone. When I mentioned this weird juxtaposition of ‘girl’ and ‘woman’ to a French-speaking friend, he mentioned that his grandmother would use jeunes filles to mean ‘unmarried women’ regardless of age. A fille could also be a servant woman, compare the English ‘maidservant’, or fille de chambre in French.

The contrast between ‘girl’ and ‘woman’ in this fragment, then, is one of worldliness, of smarts, of experience: yet they’re ‘equally stupid’. This stupidity is of course contrary to the ‘man of intellect’. The implication might be that the man of intellect would like to find something of himself in his object of desire, and you’d expect that to be the worldly woman rather than the simple girl. And yet, it turns out to be the other way around: he prefers the simple girls. Why is that?

The author doesn’t attempt to answer this, but offers it up as something to ponder. Since we’re playing the philologist, the best thing we can do is to explain the author through context. And what context is better than other things that the author himself wrote? As it happens, I think the author has mostly answered his own question with another passage from an earlier work:

Nous aimons les femmes à proportion qu’elles nous sont plus étrangères. Aimer les femmes intelligentes est un plaisir de pédéraste. Ainsi la Bestialité exclut la pédérastie.

(Fusées, folio 6)

We love women more the stranger they are to us. To love intelligent women is the pleasure of a pederast. Even Bestiality excludes pederasty.

Again the notion of paedophilia surfaces, this time in the form of pederasty, which is sexual intercourse with boys. It is the pleasure of a boy-lover, Baudelaire writes, to love women who are intelligent. An association between intelligence and masculinity would help explain the passage we started with: intelligent women are more like men, Baudelaire says. And we don’t like what we are ourselves.

This kind of view was, as far as I know, perfectly common at the time. Though slightly earlier and in Germany, Friedrich Kittler discusses in his Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900 how the formalization of universities towards the end of the 18th century also led to the exclusion of women. Before then, it’s not that women had been enrolling en masse, but there wasn’t anything legally against them doing so – and some did in fact enroll. But then came the state with its agenda to produce useful male citizens, and women came to be excluded.

Some kind of association between masculinity and intelligence still exists today, if less explicit. As suggested by pieces like Marry a Woman Smarter Than You, there is at least some pressure for the man to be the ‘brains’ in a relationship. The reverse of that coin might be a pressure on women to act as if they were stupid. And there has been some hubbub as of late when a recently published paper indicated that women are smarter than men on average. Even without discussing the merits of the paper or its claim, the fact that it stirs the pot is itself an indication of the opposite being a commonly held view, namely that men are smarter than women.

Another function of such a view, though, might be a pressure on men to appear intelligent more generally. And as I did some digging, it looks like some of this pressure might come by through mechanisms of mate selection: according to a paper by Fisman and others, women use ‘such attributes as ambition, intelligence and social status’ to gauge ‘earning potential’.1 Make of that what you will. Men were more interested in whether the woman was attractive, and based on what Baudelaire wrote, we can probably assume it wasn’t ‘earning potential’ he was looking for. If he had any Hintergedanken, they will have been something quite different.

Fisman, Raymond, Sheena S. Iyengar, Emir Kamenica and Itamar Simonson. 2006. ‘Gender Differences in Mate Selection: Evidence from a Speed Dating Experiment.’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(2): 673–697.