The Art of Slow Reading, Part 1

Learning to read slowly with Friedrich Nietzsche and Thomas Bernhard

This will hopefully mark the beginning of a long and prosperous series. One of the most fun things I know is close readings. And you cannot do close readings quickly. Hence, I thought a series of reading slowly might be the best thing to do. My concussion symptoms have dwindled enough now that I’m back in full-time employment, so I hope to post more regularly this autumn.

With that said, I do hope the title puzzles you. When slow reading is an ‘art’, one of the implicatures is that slow reading is desirable and probably difficult. This goes against what our society tends to think of as good: think of being a slow reader. You slog through texts while the others sprint to the finish line. Then you’re also presumed to be a slow learner: reading speeds should be high, information extraction should be maximized. But a lot of the time, at least if you’re reading something actually worth reading, to read fast is to read thoughtlessly. It is failing to see the uncertainties and limits of language and meaning.

The most interesting work happens on the borders of meaning. I find this is true in literature and indeed true of most things. These limits are difficult to find and hard to navigate. You lose your footing and stumble. When that happens, you have a good indication that something interesting is going on. It’s worth underscoring that this is not a mere Luddite approach to learning and information, a yearning for the Gutenberg Mind, but in fact what is necessary for deep understanding.

Nietzsche

The art of slow reading is discussed by Nietzsche in the fifth and final section of the preamble to Morgenröthe:

One has not been a philologist in vain, one is perhaps still a philologist, which is to say, a teacher of slow reading: — finally, one also writes slowly. Now it is not only to be found among my habits, but even to my taste, — a wicked taste, perhaps? — to write nothing that doesn’t bring that species of man, who “is in a rush”, to despair. Because philology is that venerable art which demands first and foremost one thing from its worshiper, to step aside, to give oneself time, to grow quiet, to grow slow —, as a goldsmith’s art or connoisseurship of the w o r d, which has only the most delicate work to perform and which accomplishes nothing if it is not lento. That is precisely why this art is more necessary today than ever, precisely because of this does she draw and enchant us so strongly, in the middle of an age of “work”, to wit: of haste, of indecent and sweating hastiness, that immediately wants to “be done“ with everything, even with any old and new book: — but the art itself does not so easily finish anything, it teaches to read w e l l, which is to say slowly, deeply, with eyes cast back- and forwards, with hidden intentions, with doors left open, with sensitive fingers and eyes . . . My patient friends, this book desires only consummate readers and philologists: l e a r n to read me well! —

This is, I find, fascinating reading (and I hope to have captured some of the rhythm of Nietzsche’s German; the unusual punctuation and letter spacing is a calque, pretty much, of the original). As it often happens when I read Nietzsche, I get the feeling that the things he was describing a century and a half ago have only been amplified further in the time since then.

A key phrase here for me is the analogy of a ‘goldsmith’s art or connoisseurship of the w o r d’. Since ‘it has only the most delicate work to perform’, the work has to be done ‘lento’ or ‘accomplish nothing’. This is a kind of reading that ‘modern man’ eschews: maximal information extraction is the name of the game. This man’s idea of an ideal language is probably Basic English or perhaps instead Bertrand Russell’s notion of an unambiguous language (an unworkable abomination); assign to every smallest entity a Universal Resource Identifier (URI), to every composite entity another URI, assign finally to the universe its URI, and you are well on your way to a universal language.

Language as it has been spoken and written by humans, however, is a different beast. It functions precisely thanks to its lack of absolute precision. We must accept with Ferdinand de Saussure that the relation between a word and its meaning is arbitrary (or quite nearly so). We must accept that disambiguation is necessary a lot of the time, though of course humans are so good at it that we tend not even to notice that we do.

Bernhard

Human language being what it is, we can find much truth in Thomas Bernhard’s novel Alte Meister (‘Old Masters’). The key person in the story says:

At home I haven’t read a book for years, here in the Bordone hall I have already read hundreds of books, but that doesn’t mean that all these books in the Bordone hall have been finished, I have never in my life finished a single book, my way of reading is that of an extremely talented leafer, which is to say that of a man who prefers leafing to reading, who leafs through dozens, and in some cases hundreds of pages before reading a single one; but when this man reads a page, he reads it more thoroughly than any other and with the highest reading passion imaginable. I am more a leafer than a reader, you must be aware, and I love to leaf as much as I love to read, in my life I have leafed a million times more than I have read, but in leafing I have always derived at least as much joy and have had at least as much intellectual delight as in reading. It is, after all, better all in all to read only three pages of a four-hundred-page book a thousand times more thoroughly than the average reader who reads everything, but not a single page thoroughly, […]. It is better to read twelve lines of a book with the highest intensity and in this way to reach through to the whole, as it is possible to say, than if we read the entire book like the average reader who at the end of the book that he has read knows precisely as little as a traveller by plane knows the terrain that he is flying over. He doesn’t even notice the contours. This is how people today always read everything on the fly, they read everything and know nothing.

Three beats four hundred, so long as you read them properly. That’s almost something Heraclitus said once, in a way: ‘One man is better than ten thousand if he is the best’. In education we could perhaps relate this to the so-called 2 sigma problem of Benjamin Bloom: a tutored pupil is two standard deviations better than the pupil who attended normal classes. There’s some discussion now whether AI tutors can solve this problem (I hope they can), but let’s do some slow reading of our own while we’re here.

Kittler

A book that I’m revisiting now after my essay on Defining Information Ages is Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900 by Friedrich Kittler. It’s a book that I find fiendishly hard to read not just because of his reliance on concepts borrowed from people like Lacan, whose works I’m all but completely ignorant of, but also because of his rather intractable style.

The normal English translation of the title is ‘Discourse Networks 1800/1900’. But I’m not sure I like this title: the German words Aufschreibesystem and Diskursnetzwerk both show up in the book. Discourse networks is a term that comes, as far as I know, from Foucault – or that at least is based in Foucault’s approach to discourse analysis. It’s used and drawn upon by Kittler, but it is not the same. I suppose Aufschreibesystem can be viewed as an extension of Foucault’s term. I will opt for the translation ‘recording system’, but English doesn’t readily offer a good translation, in my opinion, for ‘aufschreiben’.

Das Wort Aufschreibesystem, wie Gott es der paranoischen Erkenntnis seines Senatspräsidenten Schreber offenbarte, kann auch das Netzwerk von Techniken und Institutionen bezeichnen, die einer gegebenen Kultur die Entnahme, Speicherung und Verarbeitung relevanter daten erlauben.

What a beautiful sentence – pedantic, meandering and not quite serious, saying just what it needs to. Now in translation:

The word Aufschreibesystem, as God revealed it to the paranoid consciousness of his Senate president Schreber, can also designate the network of techniques and institutions that allow a given culture to extract, store and process relevant data.

(first sentence of the ‘Nachwort’ to Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900, 2nd edition)

With this definition in mind, let’s turn to a more or less random page that deals with the recording system of about 1800. As a general contextual clue, I think we can say that for Kittler, the spread of the ‘sounding method’ (Lautiermethode) of learning written language marks a technological pivot from a time when writing was reserved for the elite.

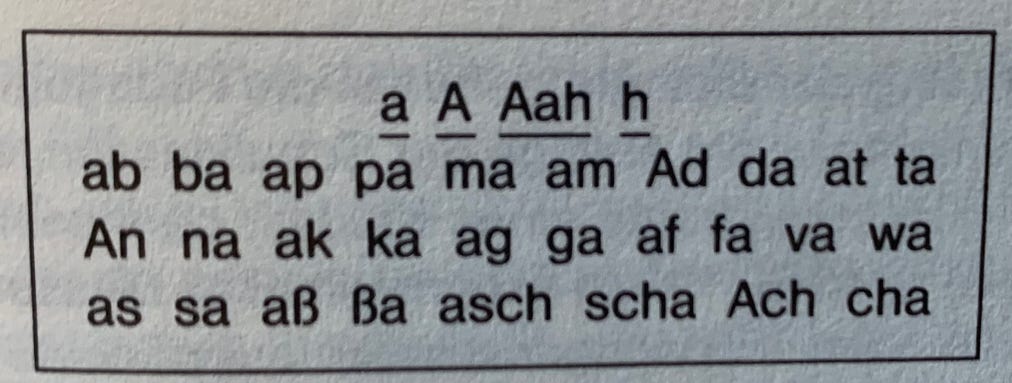

Am Anfang, mit anderen Worten, steht der Laut und nicht der Buchstabe a; vom uralten Anfangssymbol Alpha aus würde kein Weg zum Aah führen, den ja nur eine Stimme durch Färben, Trüben, Dehnen des Unbestimmten bahnen kann – leuchtendes Beispiel einer Augmentation. Derartige Dehnungen, und zwar nach Maßgabe der Silben-“Bedeutung” (!), hat schon Moritz als Deutsche Prosodie beschrieben und damit Goethe in den Stand versetzt, seine Iphigenie zu versifizieren.

(p. 53, 2nd ed.)

In the beginning, in other words, stands the sound and not the letter a; from Alpha, the ancient symbol of beginning, no way would lead to Aah, which only a voice through its colouring, clouding and stretching of the indefinite is able to reach – a shining example of augmentation. Such lengthenings, and at that according to the syllable-‘meaning’ (!), Moritz has already described as German prosody and as such enabled Goethe to versify his Iphigenia.

Among the more obvious highlights is the allusion to the opening of the Gospel of John: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ The ‘Word’ has been relegated to a parenthetical adverbial phrase, and in the place where John placed the Word, Kittler places the sound. Not the letter a, or alpha, the first letter of the Greek and Roman alphabets, which we know from phrases like ‘alpha and omega’, where these two metonymically encompass and include everything. We sense a certain irony, then, in the faith that the turn of the 18th to the 19th century had in their Lautiermethode.

The parenthesised exclamation mark is the next thing that catches the eye. In a way, it’s this exclamation mark that holds the key to the really quite puzzling passage.

Now, we presumably are familiar with Goethe, we might even have read his tragedy Iphigenia (I haven’t), but this Moritz figure is probably unknown to pretty much all of us. Thankfully, we don’t really need to work out who Karl Philipp Moritz was or what he says in his work on German prosody. It’s enough to track down a passage from Goethe’s Italian Journey:

I would never have dared translate Iphigenia to iambics if I hadn’t found a guiding star in Moritz’s “Prosody”. Talking to the author, in particular at his sickbed, has brought me further clarity about this, and I request my friends to think back to this with kindness. [Moritz was dead at this point.]

It’s striking that we in our language can find only a few syllables that are definitely short or long. With the rest, you proceed according to taste or at random. Now, Moritz has worked out that there is a certain rank among the syllables, and that the one with a weightier meaning is long when facing a less meaningful syllable, and in turn makes the other short, but will itself become short when in the proximity of a syllable with still more spiritual weight.

Syllables, in short, were taken to have an intrinsic meaning of sorts. But what can a syllable mean on its own? Saussure hadn’t yet entered the scene and was yet to make a big splash with his thoughts on how sound and meaning were unconnected. In Goethe’s time, around 1800, the idea that there was a preponderous connection between a syllable’s meaning and its length might have seemed very reasonable. When Kittler inserts a question mark in a parenthesis, however, it’s easy to read as a knowing question mark, something quite similar to writing sic!, signalling that you know much better than the author you’re quoting.

But if we were to return to Bernhard’s words and think that we would gain more understanding from reading a few more lines in addition to these few than we would have from skimming through the entire book, I’m not so sure. I don’t think it’s possible to read Kittler’s thesis about the interaction of media and society out of this simple passage, a thesis where technology takes over from culture the role of determining the course of cultural development. Nor would it have helped much to expand the passage. But we have perhaps learned a fair bit about Kittler and his way of writing on the one hand, and a bit about what kind of hard work it can take to understand just a brief passage in a four-hundred-page tome.

Inspiring! As a massive amounts of superficial information enjoyer, I suspect some slow reading could do me good. Unfortunately I read this while my daughter was furiously «trying to sleep» so I suppose I’ll have to do it again later. Or maybe just a few lines, but really intensely!