Introduction

We talk and write without thinking about it. We absent-mindedly exchange spoken information and for younger cohorts, sending a message on social media seems as natural as talking. While literacy is a term that I think most people will have some associations with, orality is somewhat nebulous. A glance at the Oxford English Dictionary tells us that except for an apparently isolated usage of ‘orality’ in 1666, we had to wait until the 20th century for ‘orality’ to make its appearance. The first of these were, to my surprise, from psychoanalysis. There, the word meant oral fixation – in a sexual manner. That’s not why we’re here though. This post is intended to be the first instalment in a series on literacy, and as such, the main goal will be to set the stage for the following posts. I will try to do this by writing a brief history of literacy and orality.

For my own part, I came into touch with literacy and orality at an enthusiastic talk for students at the Classics Department in Oslo held by a professor emeritus. Jack Goody, Eric Havelock, Walter J. Ong and Marshall McLuhan were the old champions of literacy and orality as important medial technologies that shaped the human condition. McLuhan was interested, I think it is fair to say, mostly in media as such, and his The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) is a strange concoction of references to various authors and historical events that almost becomes aphoristic in style, and carries the revealing subtitle The Making of Typographic Man. The core idea is that print really released the power of writing and gave it a potency that handwriting did not possess.

McLuhan’s book has found echoes in recent work such as Jeff Jarvis’s The Gutenberg Parenthesis (2023), where the notion is that the ‘Gutenberg era’ of literacy constitutes a finite period in history and that we are returning to a ‘pre-Gutenberg’ state now with the mass adoption of digital media, with audiovisual media in the form of videos and similar things being everywhere (TikTok, say). I don’t know to what extent I agree with such an analysis, but considering things like the decline in students’ reading proficiency, it does have an appeal.

Some time after his Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhan made the statement that ‘the medium is the message’. This idea will prove a core notion in taking a closer look at literacy and orality: we’ll be studying the medium of communication and its consequences. As the very words indicate, orality is communication through spoken language and literacy denotes communication through letters. The question then becomes how spoken and written language have shaped people and society – or if they have at all.

McLuhan’s core idea was that media revolutions shape humans and our societies. His views come close to what we might call technological determinism, where the introduction of writing on the one hand, and then the invention of movable type, would necessarily lead to developments akin to the ones we have had in the West – that is to say, an increasing amount of ‘rationality’, consciousness and institutions. No humble claims, in other words. With radio and television, McLuhan surmised, we would be returning to an oral society, a ‘global village’. But instead, digital, so-called social media now appear to silo people according to opinions and interests – according to maximum engagement, in a word. Rather than a ‘global village’, maybe we have myriad global tribes in constant conflict with each other. Although McLuhan’s ‘global village’ seems not to have manifested itself, the idea that media change people and society seems to have more heft to it.

‘The Greek Miracle’

The notion of a Greek miracle is older than the study of writing and literacy. The first attestation that I’m familiar with comes from Ernest Renan’s “Prière sur l’Acropole” (“Prayer on the Acropolis”), where he relates a religious experience he had when he visited the Acropolis (it can be read in English translation here). Presumably, though, the notion has Renaissance and Humanist roots, where Antiquity became a symbol of shining light opposed to the so-called Dark Ages of Europe in the period that came between the Ancients and the Humanists (a narrative that is, as all simplistic narratives must be, perfectly false).

In the 20th century, two of the chief proponents of a ‘Greek Miracle’ were the two Germans Wilhelm Nestle and Bruno Snell. The former wrote a book called From Myth to Reason (Vom Mythos zum Logos, first published in 1940). The argument is largely as the title implies, namely that the Greeks progressed from a mythological worldview and way of thinking to a logical worldview where reason dominated. As early as in 1951, though, this was to meet with stark criticism: E. R. Dodds, an Englishman far less interested in any sort of Hegelian progression of history than Nestle, published The Greeks and the Irrational. Nestle is very much outmoded today, while Dodds is read with delight.

A compatriot of Nestle, Bruno Snell’s Die Entdeckung des Geistes (1946, expanded edition in 1948) is a book that was given the English title The Discovery of the Mind, which is misleading inasmuch as the German word Geist also means ‘spirit’, for instance. To put it a little too simply, the book traces how the Greeks ‘invented’ consciousness. Today, my impression is that the book is cited mostly for its philological work, not for its grand vision. But I think this warrants a closer look at a later time.

Enter Orality

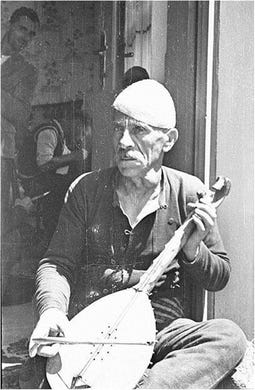

Only in the 1970s and 1980s did orality really become a thing. This might seem a bit odd, but looking through Milman Parrys’s work, the word ‘orality’ simply isn’t found.1 Parry studied the Serbo-Croat guslars in Yugoslavian backwaters. They were ‘illiterate’, and they could sing songs of incredible length. Parry’s work was originally on epithets in Homer, and based on his ethnographic work with the guslars, he concluded that Homeric epithets were tools in oral poetry – they neatly fit in a given place on a given line in a given metric scheme, and this formal placing, he concluded, was their sole purpose.

Even if later work has nuanced this stance, I think it must be said to be broadly correct for a lot of oral poetry: it tends to make use of specific meters and formulaic phrases partly as mnemonics and partly as the building blocks that permit their extensive oral compositions in the first place. Together with Albert Lord and his book The Singer of Tales (originally published in 1960), they thus came to define oral literature: in their account, the oral poet improvised the poem on the spot by drawing on a wellspring of traditional jigsaw pieces according to established poetic norms. This meant that you could draw a clear line between improvised oral literature and carefully revised written literature.

Criticism of Previous Accounts of Orality

As popularized by McLuhan, Havelock and perhaps especially Walter J. Ong in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, orality came to signify – or at least strongly imply – that there is a marked divide between literate and oral cultures. In some sense, this seems plainly true – after all, written cultures read and write, and oral cultures don’t. Instead, oral cultures must convey information orally (duh).

The distinction can be overstated, however. This can perhaps be said to be the main argument of Ruth Finnegan’s book Literacy and Orality: Studies in the Technology of Communication (1988), even if the book is a collection of papers with the earliest having been published in 1973. Her work consisted to a large extent of looking at the great variety of oral cultures. In particular, she shows how oral performance is not always improvised ex tempore (‘out of the moment’, though tempus more often means ‘time’). In a pacific culture discussed by Finnegan, poems are carefully composed and memorized before they are performed. And though their texts (oral texts!) may change in performance, that doesn’t change the fact that their work is by and large fixed before they are performed. This is a stark deviation from the guslars that Parry and Lord took to be the paradigmatic example of an oral poet.

Another example is that physical mnemonics are frequent in oral cultures, and they bear some resemblance to writing. I think this point might be overstated, because humans have been creating artifacts for a lot, lot longer than they have been using writing. The flip-side of the coin, however, is that literacy is also a good deal more varied than had been assumed in previous work. If that’s the case, then how could reading and writing really be said to have a given set of implications?

The Literacy Myth

The Literacy Myth is a 1989 book by Harvey J. Graff. It shows how the belief that literacy is both a necessary and a sufficient condition for a society to become civilized, develop economically, and basically any kind of societal good connected to civilization, is a myth (albeit with a 19th century backdrop in this case). In a sense, Graff can be said to continue the work of Finnegan that I briefly outlined above. In her view, the literacy/orality dichotomy is one of many such dichotomies, where literacy is tied to the ‘positive’ side of civilization/primitive and so on, while orality is tied to the ‘negative’ side, although his emphasis is different.

This literacy myth has probably been, to some extent, ‘innate’ in Western culture since at least the Enlightenment. Nonetheless, I believe it is fair to say that the works of Parry and Lord will have helped perpetuate these distinctions. If we take Lord’s The Singer of Tales as our point of departure, then oral literature is taken to happen according to principles that are almost completely different to written literature. The oral poet is always improvising, the author of writing is always turning his stylus and revising what had already been written. The written work is, in the words of T. S. Eliot, only ‘abandoned’, whereas the oral work is consummated in performance. The consummation will depend on the audience, for instance: an eager audience will inspire the poet to craft a longer tale, and a disinterested one will make him cut the tale short, even abruptly so, since the interplay between performer and audience is a necessary part of the whole performance. If it dies, the performance ends. Finnegan, however, shows that this is not at all the only mode of oral literature, and she added many nuances to the discussion of literacy, orality and the role of the medium – or, if you will, the role of technology.

Like Finnegan, Graff does not oppose the idea that literacy is important. What he does oppose, is the idea that literacy in and of itself will be a force for liberation, for economic ascendancy, and for other such things that we rate as highly important in the West. UNESCO has been, Graff wrote later, one of the worst offenders in propagating literacy myths as part of their work on spreading literacy around the world. Graff is not opposed to making people literate, but that a one-size-fits-none solution should be imposed on cultures and peoples of every ilk; literacy, he points out, has been adopted in various ways by various cultures. It simply does not do to force everyone into the same mould regardless of circumstance and context.

The Path Forward

While I don’t know enough to provide a full account of the current situation when it comes to literacy and its perhaps at least partly mythical effects, what I can do is give some of the topics that I intend to discuss in the series going forward. The status quo today appears to be largely a mix of the Graff-like approach where the effects or consequences of literacy are highly contingent or uncertain and the UNESCO view that literacy is the foundation of turning developing nations into developed nations. But I do think that there are good grounds for a fresh look at this whole debate.

For instance, there are good reasons to believe that literacy does have a host of effects. Some of these are individual, and may be purely cognitive, so to speak. In The Mind on Paper (2016), for instance, David R. Olson discusses how reading and writing is connected to consciousness and rationality. A closer look at how will be one of the instalments in this series.

Similarly, Andy Clark in The Experience Machine (2023) has, as one of many examples and discussions, an account of a person with a severely impaired memory who, through the aid of a notebook where he writes down things he has to know and remember, functions like a person with normal memory would. This notepad should, according to Clark, be considered part of this person’s consciousness. If consciousness is a memory system (see Budson et al. 2022 for one such account), then it will indeed make good sense to view the notebook as an extension of the forgetful person’s consciousness. And then, as a consequence, we might again start to take McLuhan’s idea of media as ‘extensions of man’ quite seriously, though perhaps in different ways than he had originally imagined.

To touch more concretely on my plans going forward, though, I fancy that it will be a good idea to start with getting a better idea of what writing is, how it came to be and how it works. After all, writing has been through quite a lot of changes in the five millennia it has existed. The same goes for reading, which can be viewed as the decoding of the information that writing encodes, and reading might need its own instalment. Oral literature is an immensely fascinating field, and my experience is that it can be quite difficult to envision how oral literature works. This will also be an instalment.

These closer looks at oral literature, writing and reading are meant to make discussions of the cognitive and societal implications that literacy may or may not have more vivid as well as better anchored in facts. What McLuhan’s and Ong’s works, for instance, have suffered from, is at least in part that they have generalised too much. Hopefully, that is something that can be avoided in this series – though some generalising and idealisation is always necessary to reach conclusions with scope and reach beyond particular facts. In the case of the ‘birth of reason’ in Greece, we should be able to give at least some indication of how and why it happened there, and after the introduction of the alphabet, rather than with cuneiform in Mesopotamia, say.

This would be similar to how we can explain the absence of a Greek industrial revolution by the scarcity of coal necessary to fire a steam engine: even though the Greeks actually managed to make a working steam engine in Alexandria in the first century A.D. There was, however, very little incentive and very few possibilities for experimentation with this kind of engine, for the Mediterranean is in general very poor in both wood, needed to make charcoal, and in natural coal deposits, such as we find in England. The first commercial usage of a steam engine was in fact pumping water out of an English coal mine, a place where coal was abundant to the point of practically being free. That was the only place where such a wasteful engine could be used profitably. That the first steam engines were wasteful were, in other words, not a concern. Only as the efficiency of the steam engines improved, were steam-powered factories, ships and trains made possible. With this in mind, an Ancient Greek industrial revolution begins to seem like only a very remote possibility indeed.

The example of the steam engine and the lack of a Greek industrial revolution also shows us that particular facts are play a crucial role, though. At this time, I imagine that I will contrast e.g. Hammurabi’s law with law codes from Ancient Greece. Additionally, last year saw the publication of a study of Norwegian transitions from oral law to written, from written law to printed, and finally from printed law to digital. I expect that this will be a very helpful study when we reach this point (see Sunde 2023 below).

When all this is done, I reckon it would be good to take a close look at the present, where digital media flourish. At least here in Norway, the introduction of computers and tablets in elementary schools has been deemed a failure. Is this simply a new fear of change, or is there really something different about digital media that produces effects that are different from those of traditional print and so on? In particular, ‘social media’ and their effects deserve a closer look as well, though they probably don’t deserve the ‘media’ part of their name, as they are served exclusively through other digital media.

We might also ask if artificial intelligence will constitute a new medium of sorts. As of today, it looks to me like AI is used through existing media, so at least for now, I would remain sceptical of that. On the other hand, the first printed books were very similar to handwritten manuscripts, and it took a long time for print to really carve out its own niche, so to speak. Maybe a similar development will happen with AI. Even if it should turn out that AI will operate through established media, we might perhaps talk of a new ‘information age’ being ushered in (compare Hobart and Schiffman 1998). That’s also something I would like to discuss at some point.

That’s all for now, though. How this series will wind up is very much up in the air, and any comments or suggestions are most welcome.

Sources and Some Further Reading

Barber, Karin. 2007. The Anthropology of Texts, Persons and Publics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Budson, Andrew, Kenneth A. Richman, and Elizabeth Kensinger. 2022. ‘Consciousness as a Memory System.’ Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 35 (4): 263–297.

Buxton, Richard, ed. 1999. From Myth to Reason? Studies in the Development of Greek Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, Andy. 2023. The Experience Machine: How Our Minds Predict and Shape Reality. London: Allen Lane.

Couldry, Nick, and Andreas Hepp. 2017. The Mediated Construction of Reality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Dodds, E. G. 1951. The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. 1979. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early Modern Europe. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Finnegan, Ruth. 1988. Literacy and Orality: Studies in the Technology of Communication. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Finnegan, Ruth. 1992 [1977]. Oral Poetry: Its Nature, Significance and Social Context. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Originally published by Cambridge University Press in 1977, but with added material for the 1992 edition.

Havelock, Eric A. 1963. Preface to Plato. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Havelock, Eric A. 1982. The Literate Revolution in Greece and Its Cultural Consequences. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Hobart, Michael E., and Zachary S. Schiffman. 1998. Information Ages: Literacy, Numeracy and the Computer Revolution. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Goody, Jack. 1977. The Domestication of the Savage Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goody, Jack and I. Watt. 1968. ‘The Consequences of Literacy.’ In Literacy in Traditional Societies, edited by Jack Goody. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graff, Harvey J. 1979. The Literacy Myth: Literacy and Social Structure in the Nineteenth-Century City. New York: Academic Press.

Graff, Harvey J. 2010. "The Literacy Myth at Thirty." Journal of Social History 43 (3): 635–661.

Jarvis, Jeff. 2023. The Gutenberg Parenthesis: The Age of Print and Its Lessons for the Age of the Internet. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lord, Alfred B. 1971 [1960]. The Singer of Tales. New York: Atheneum.

Martin, Henri-Jean. 1994. The History and Power of Writing. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Originally published as Histoire et pouvoirs de l'écrit, Librairie Académique Perrin, 1988.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1962. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill.

Nestle, Wilhelm. 1975 [1940]. Vom Mythos zum Logos: Die Selbsentfaltung des griechischen Denkens von Homer bis auf die Sophistik und Sokrates. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag.

Olson, David R. 2016. The Mind on Paper: Reading, Consciousness and Rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ong, Walter J. 1982. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Routledge.

Parry, Milman. 1971. The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Edited by Adam Parry. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Snell, Bruno. 2011 [1946]. Die Entdeckung des Geistes: Studien zur Entstehung des europäischen Denkens bei den Griechen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Sunde, Jørn Øyrehagen. 2023. 1000 år med norsk rettshistorie. Oslo: Dreyers forlag.

Thomas, Rosalind. 1992. Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Note, however, that my investigation of this point only consists of doing ctrl+f for ‘orality’ in the article collection Parry 1971.

Fascinating introduction. I applaud your ambition in this project!

Personally I am squarely in Team UNESCO, verging on the mythical. I don’t think it’s possible to overstate the importance of such a central technology as writing. I am looking forward to having my preconceptions challenged!