Lapidary Reading

Notes on Early Greek Literacy

The lapidary in the title actually can be taken in the sense that ‘lapidary’ often gets in modern English: a lapidary statement is one that is short and polished. The prose of Ernest Hemingway or Raymond Carver comes to mind. The sense that I have in mind here, though, is writing that actually is set in stone or that is otherwise inscribed. While it is of course difficult to say whether the fact that much of the earliest alphabetic Greek writing is written in stone is thanks to the durability of the material or if it actually was one of the first ways writing was used in Ancient Greece, we have a lot of material that fits the bill.

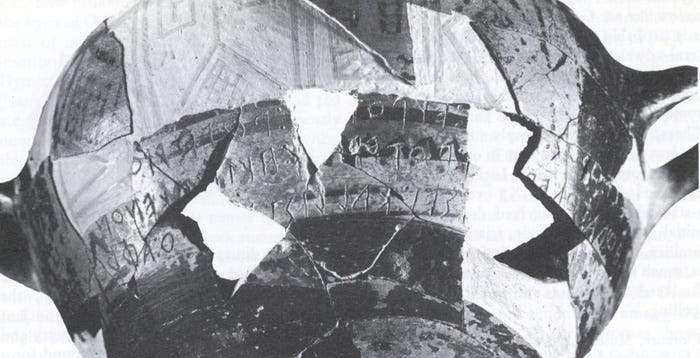

One of the very first instances of writing, the so-called Nestor’s cup (dated late eighth century BC), is also one of the most famous. The text is not quite complete, as the cup is missing some fragments, but by filling the gaps, we can get a pretty decent sense of what the text says (there have of course been many suggested emendations).

A translation might run ‘Nestor’s cup am I, good to drink from. Whoever should drink from this vessel, the desire of Aphrodite with the fair crown will seize him immediately.’ The transcription might in a sense be misleading, as it looks to us as text normally would – printed on a page. In reality, however, the text is incised into the clay of the pot before it is burnt.

In this picture, the material object is better presented. The translation I offered here has the drinking cup present itself as a cup owned by Nestor. This might be an allusion to the cup that the Nestor of the Iliad has. Further, I should highlight the fact that the remnants of the text as it is preserved on the cup, does not reveal if it is a text in the first person. That is an emendation. But it is in fact the norm for objects to speak in the first person, however strange this might seem to us.

Inscriptions on monuments were made to be read aloud (and most likely, nobody read silently at the time), so that when you read the text on a statue or something of the sort, you would lend your voice to the object in front of you. This sort of affinity with the oral is also why such early inscriptions tend to be metrical. In this case, the two final lines are dactylic hexameters, the same verse form that we find in the Homeric epics, and the first verse appears to be either prose or an iambic trimeter, another common type of verse. A stele (a grave monument in stone) from Thessaly and which is dated to the end of the sixth century BC has the following: [h]ubristâ emi nmâma, ‘I am the memorial of Hybristas.’ I was unfortunately unable to find an uncopyrighted photography of this memorial, and hence offer another, later one in its place:

The text above the two children goes: ‘Here lies this memorial of Mnesagora and Nikochares: it is no longer possible to point them out; the daemon’s fate has removed them, and they have left a great sorrow for their dear father and mother both, as [the children] have died and departed for the house of Hades.’ (My translation, following Brown 2005 in how to understand αὐτὼ δὲ οὐ πάρα δεῖξαι). This funerary poem is striking not only in itself, but as Brown points out, it is also unusual in that it highlights in an uncommon manner a paradox that was at the heart of Greek funerary rites, where the memorial was a focus point for remembrance and affection, although the ‘soul’ had departed to Hades and was beyond reach for the living.

Though this last example is at a time when the Greek alphabet was well established, I want to highlight the following question: To what end was the Greek alphabet developed? Unlike many other scripts that appear to have been made for commercial ends, the Greek script might in fact have been developed for literary or perhaps rather cultural and religious ends, such as those seen on the cup of Nestor and the memorial of Hybristas. The literary is in this period hardly separable from culture and religion. Nestor’s cup hints at the so-called sympotic poetry, which aristocratic elites might recite at their eating and drinking feasts where there would often be enslaved women playing the flute and where various carnal acts might have been on the menu. The funerary inscriptions, on the other hand, also highlight how writing was employed together with other media.

Another important end, though not among the earliest, of Greek writing, was legal texts. I hope to write more on this later, so here I will content myself with noting that although writing in many cultures was a tool for the elite to fix and fasten existing social strata, existing Greek inscriptions suggest that this was not the predominant use of legal writing. Some early legal texts, for instance, were inscribed on temple walls. As with much other early writing, they were inscribed boustrophedon, though new sections were often signalled through starting a new line from right to left. Further, scribes usually tried to make the text readable – something that would not have been a priority, presumably, if the text was intended mainly as an imposing monument of oppression. Punctuation of various sorts was common, usually sectioning off some sort of phrase, such as the use of commas to demarcate this incomplete sentence, rather than full periods. In other words, the punctuation appears to have been aimed at facilitating reading.

Another thing that, in a sense, is foreign to us, is the visual aspect of many inscriptions. Many monumental inscriptions are written with what is known as stoichedon, which is to say that the letters are aligned vertically and horizontally. The result is not particularly pleasant to read (for us, anyway), but has a powerful and imposing visual effect.

But even on this inscription, with its impressing arrangement of letters, we see that there is some punctuation to aid the reader. To sum up, I will quote half a paragraph from Rosalind Thomas, who in 1992 wrote the following (Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece, p. 65):

So to a large extent archaic Greek writing does seem to be at the service of speech, [by way of] repeating verse, enabling the objects to “speak” as if they were animate, preserving and reinforcing the pre-literate habits of the society, extending and deepening the customs of poetic and visual memorials.

It is perhaps best to be cautious, but it really does seem to be remarkable that the Greek alphabet does not appear to have been developed for commercial ends. Though later work, as I wrote in my previous post, has tended to moderate the earlier claims of the effects of literacy, I want to draw attention to the fact that writing in archaic Greece – or at least what is preserved – is often hewn in stone or carved in clay. Others are scratched on pottery shards. If there is a distinction between what Ong called chirographic and typographic writing on the one hand and what I here have called lapidary writing on the other, then it would make sense if there is a sort of shift, at some point, from the earliest signs of literacy and on to the later, more familiarly literary ends that writing was put to in Ancient Greece. It should perhaps not surprise us, then, if the writing of the archaic period fails to display the effects that pioneers in the domain of literacy were so eager to ascribe to the effects of writing. These effects, according to these pioneers, are envisioned to stem from the objectification of language through being confronted with one’s own thoughts on something like a wax tablet such as that pictured in my first post or on a papyrus.

FURTHER READING

Andersen, Øivind. 1987. ‘Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im frühen Griechentum’. Antike und Abendland 33: 29–44.

Gagarin, Michael. 2008. Writing Greek Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, Rosalind. 1992. Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.