As I am about to embark on what I hope will be a productive and enduring venture, my thoughts hark back to what Siegfried Sudhaus wrote in the preface to his 1892 edition of Philodemus’s work on rhetoric:

If I could, I would rather have retained and revised these volumes of Philodemus on rhetoric. But there are many things that move me to finally publish what I have. For not only does the education or instruction of our youth increasingly call me away from the subtility of my studies, but every passing day increases the desire for broader reading, and so it seems I must put an end to this endless labour. In addition, I know by experience that a work is made better by the discussion of many and the judgment of philologers than by that of one person. (my translation)

Si possem, haec Philodemi de rhetorica volumina retinerem et retractarem potius quam ederem. Sed multa me commovent, ut quae habeam tandem edam. Nam et puerorum vel educatio vel institutio me ab hac studiorum subtilitate magis magisque revocat et amplioris lectionis cotidie movet desiderium, et infiniti laboris aliquis tandem finis faciendus videbatur, et complurium contentione et iudicio philologorum plus effici quam unius opera expertus scio. (source)

Though appreciating the antagonistic nature of scientific proceedings typical of the modern period is of a newer provenance, in being reluctant to publish his works, Sudhaus is following an ancient practice.

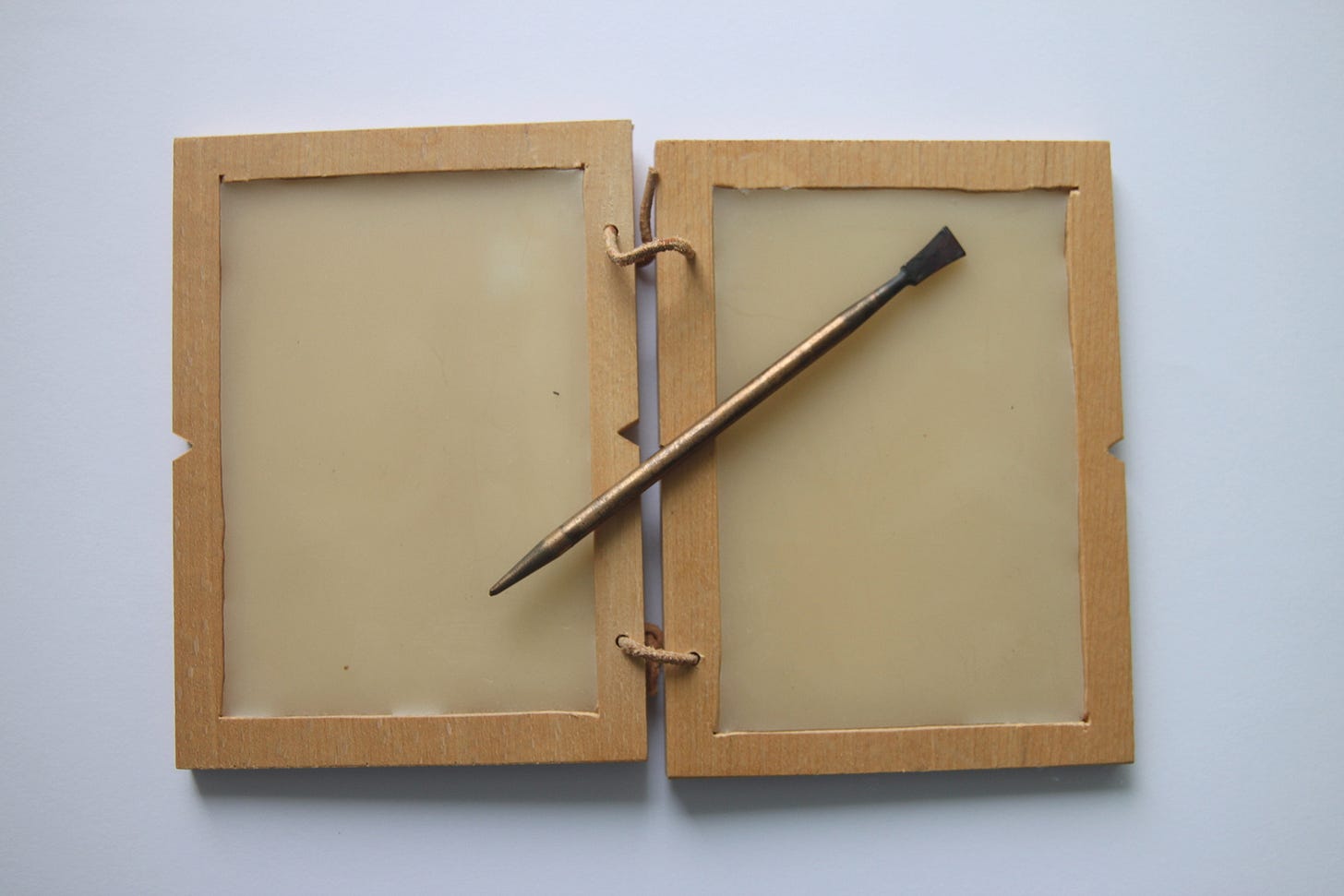

The best-known example will probably be Horace, who admonished would-be poets to flip the stilus often: ‘Turn your pen (stilus) often if you aim to write something worth re-reading’ (‘Saepe stilum vertas, iterum quae digna legi sint | scripturus’, Satires, I.X.72–3). The back-end of the stilus had a broad end for erasing what you had written on your wax tablet. To flip it often is to revise diligently.

Stilus with wax tablet. Copyright Peter van der Sluijs. Copied from Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Of course, at some point you must publish. Horace knew this, and Sudhaus did too. As did Paul Valéry when he wrote that in the eyes of anxious people who aim for perfection, a work is never completed – this word, he wrote, does not even make sense to such people – but only abandoned (‘Aux yeux de ces amateurs d'inquiétude et de perfection, un ouvrage n’est jamais achevé, – mot qui pour eux n’a aucun sens, – mais abandonné; …’ (source – I consulted a physical copy)).

As a matter of practicalities, a writer can hardly be called a writer unless something is not only written, but also published. Historically, though, we have not always had writers at all. Classical Athens might in some way be an example of a society in which many writers were not first and foremost writers, but performers. This could go for a person like Demosthenes, who performed his own speeches which only subsequently were published, but not for a person like Lysias, who wrote speeches for others; as Lysias was not a citizen but an immigrant – a so-called metic – he lacked the right to speak publicly. There is only one exception, namely his speech Against Eratosthenes.

Owing to their efforts in thwarting the Thirty Tyrants, he and other immigrants were granted citizen status by a proposition that was later revoked as what we would call unconstitutional. With this speech, Lysias prosecuted Eratosthenes – one of the thirty tyrants that held sway over Athens for a period after the end of the Peloponnesian war – for the murder of his brother.

Demosthenes, on the other hand, we know only as a writer, but his contemporaries would have known him as a speaker. Lysias, on the other hand, would have been known not only for his personal wealth – he and his brother were heirs to a shield factory which is to have employed more than a hundred slaves – but also for the forensic speeches he produced for others.

Where both Demosthenes and Lysias ultimately were productive writers, Isocrates strikes a different pose. He is the oldest example I can think of that embodies the anxious and ever-revising writer. Supposedly born with a weak voice, he was not carved out for the great Athenian debates where speakers frequently would be shouted down. He turned instead to what he called philosophy, but which we would be more likely to recognize as rhetoric (the schism between the two was, in other words, yet to be invented). It is always difficult to separate invention from truth when dealing with the biographies of ancient writers, but from what Isocrates has left us in the form of written works, it seems clear that he placed a very great emphasis on a sort of stylistic perfection that would appear incompatible with the heated political debates of the Athenian council – a council with 400 members and no microphones – not to mention the assembly, where a meeting could regularly contain 6,000 people.

The stylistic perfection of Isocrates is perhaps best recognized in the almost total absence of what’s known as a hiatus. A hiatus is a pause, in this case between two vowels. Though this is not really felt in English, the collision of two vowels produces an ever so slight pause. To the Greeks, this was no good. But as in English, to constantly avoid setting two vowels next to each other is almost impossible, and even more so in Ancient Greek, where words could end only in vowels and the consonants e, r and s. To achieve this end, Isocrates tortured his writings until they yielded.

I have no such intentions. The goal of these meanders is simply to say this: that I will publish no piece so polished as to be perfect (which means that excessive alliterations might at times slip through). I remain hopeful, however, that whatever sins I commit will provide ample grounds for disagreement and growth.